24 Jul Synchronicity

Oleg Stavrowsky recognizes that not everyone passionate about Western art finds meaning in his most recent paintings. He dedicates himself less and less to the visual truth of Realism. More and more he explores the illusory nature of both contemporary and historic Western subjects. Thus, when we view his newer canvases, we won’t see iconic Western figures presented in familiar settings. We won’t find an obvious story, or what we already think we know.

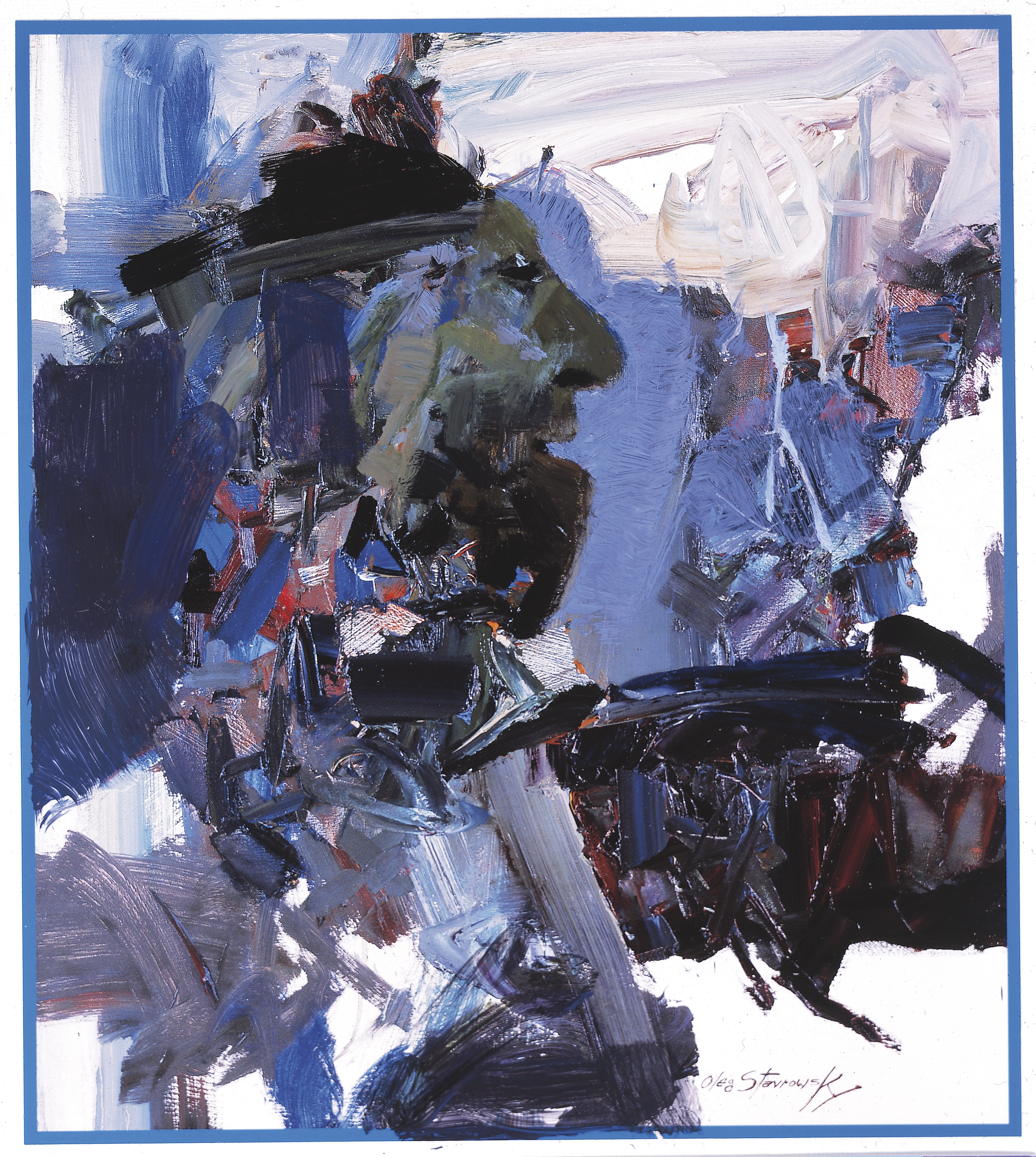

“The idea is to paint Western abstracts,” Stavrowsky explains from his home in Texas. “I want to keep the Western flavor alive and well. I want to do that by giving it as much obvious statement as I do to the abstract end of it. It’s very, very difficult to do. It’s both a design and emphasis problem. Not so much size-wise, but in its importance in the painting.”

Stavrowsky bridges his avant-garde conundrum with colors, forms, lines, sweeps, textures and vivid imagination. He asks us, his viewers, to take our time exploring his abstract pictures, to dig a little deeper for him and pop open our minds to the expressive experimentation he himself invests as a painter. He offers a hint: “The title can give the viewer some direction as to what to look for, or at. The viewer decides the story and hopefully will understand that whatever is interpreted will be tinged with the Western genre.”

In his recent Winter Kill Shaker, Stavrowsky creates a chilling, stark place. At first there seems no sensible explanation for the creature’s presence, or even a sense of what it is, for that matter. Yet, its expression communicates malice, evil. Consider the thing’s roundness, the stout appendage at its top, the beige, ashen and russet colors. Apply Stavrowsky’s hint: Winter Kill Shaker, and then on to an allusion of shaker. In Native American culture, shakers were important instruments in ceremonies that summoned benevolent beings or repelled evil ones. Shakers represented supernatural connections to the spiritual and natural worlds. Given this, perhaps Iya, the evil being the Lakota Sioux blamed for disease, starvation and war, transcended the two worlds — in the form of a shaker.

Present Stavrowsky with this nonsensical interpretation of Winter Kill Shaker and he may nod.

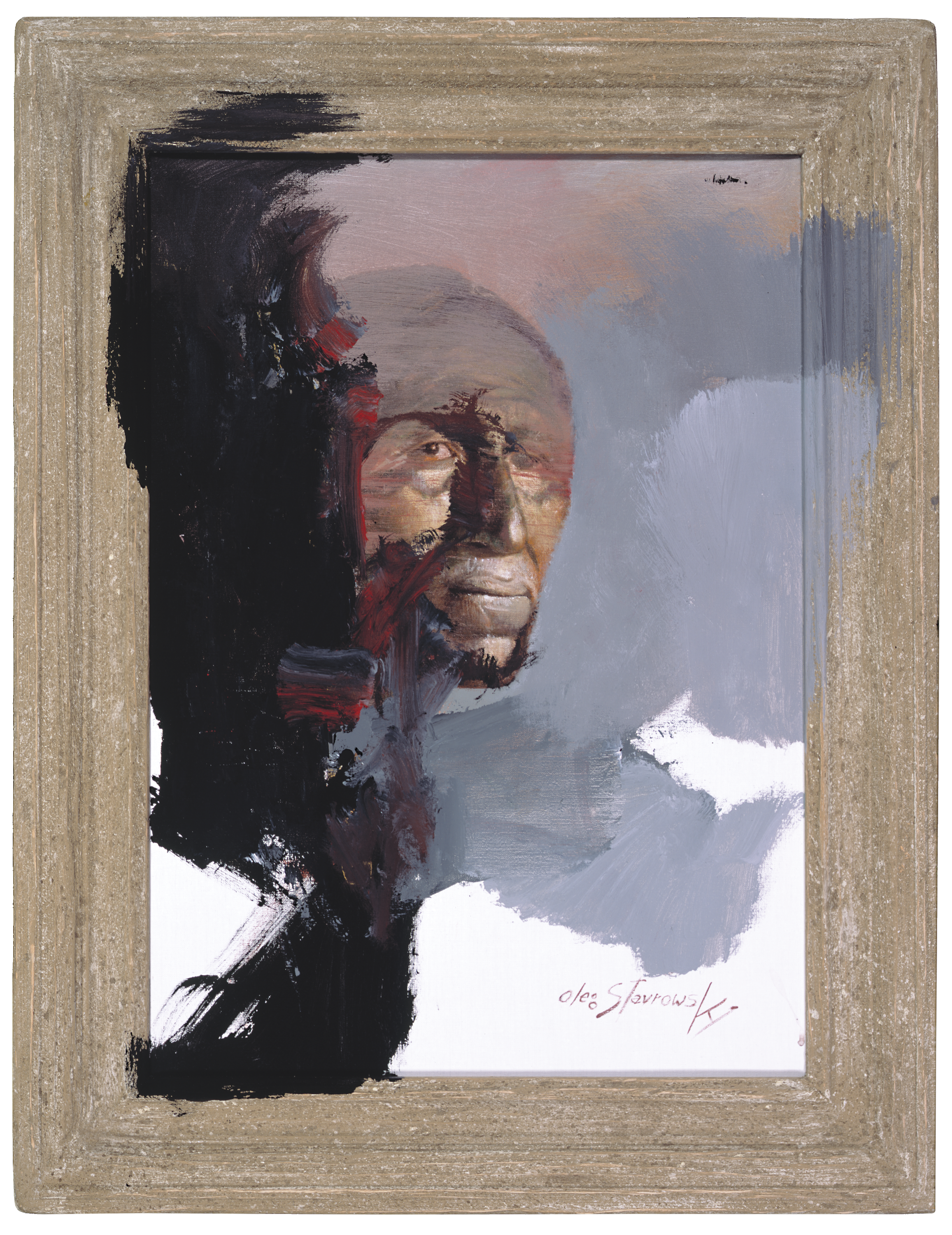

Another new work, Vanishing Indian, is less enigmatic but just as compelling. Horizontal brush strokes across the Indian’s disquieting face suggest textured, striated landforms. Creamy pink, ochre and shades of brown infer the soft, muted colors of the West’s buttes and rock walls. In a poetical sense, Native Americans are as old as the land on which they live. Swashes of gray and brick red punctuate the canvas, heightening its drama. With the settling of the West, much of the Indians’ way of life, inextricably linked to the land, vanished amid chaos and desperation.

Stavrowsky may give a noncommittal nod at this historical interpretation. He is purely a visual storyteller, and if asked, would not divulge the elements that inspire his pictures. Nor is he an apologist about the inequities or exploitation that shaped our nation. “To me it’s simply fascinating history, uniquely ours,” he offers.

Stavrowsky’s artistic career began at age 30 in the trenches of commercial illustration. There he refined his ability to draw and developed a work ethic of exacting standards in the face of unbending deadlines. In 1969 a serendipitous assignment took him to Oklahoma City. “I didn’t know Western art existed until I walked into the National Cowboy Hall of Fame,” he says. “I was hooked. I reasoned that if I could paint a sweaty bottle of beer, I could paint a horse.”

A city boy who was born and raised in Harlem and spoke with a New York accent to boot, Stavrowsky gave up his lucrative career to become a Realist painter of the American West. He sequestered himself in museums and libraries to pore over books and historic photos featuring cowboys and Native Americans, the freighter and his team of animals, the Jehu and his stagecoach, and other things Western, to ensure the historical accuracy of his pictures.

For a time, he and his wife, Carol, settled in Santa Fe. In honky-tonk bars Stavrowsky drank with contemporary cowboys, memorizing how they dressed, stood, smoked a cigarette and chewed tobacco. Behind the bucking chutes at small town rodeos he studied the rigging and other gear strapped to the broncs and bulls. On the range he studied the curves and lines shaping longhorns; he studied the swirl and color of cowponies’ hair. He listened patiently to Western music (which he eventually grew to like) and relentlessly scrutinized the work of James Reynolds who, Stavrowsky says, was the absolute top Western Realist painter of this generation.

In Santa Fe 20 years ago, Stavrowsky met Rocky Hawkins, a leading and pioneering Native American Abstract Expressionist artist. Says Hawkins, “Within a quick first glance at his explosive and very aggressive painterly paintings, I knew he would become my most treasured mentor and friend. You could say we are both rebels of a sort. We’ve developed a longtime relationship challenging the norm. We are the best of friends but to this day continue to steal the inspirational jazz from each other’s paintings. We are in awe of each other.”

Stavrowsky, now in his 80s, is one of the West’s most sought after artists. He is not affiliated with any gallery or agent, works strictly on his own and primarily on commission. Through all of this, Carol has been his anchor, supporting and championing the artist’s life work. And Stavrowsky wants even more. “I want to do great imagery,” he says. “A good painting never leaves you alone. You return to it because it keeps beckoning to you to tell you all about itself. It doesn’t blend into the wallpaper and you don’t have to talk about it. Artists who do that are telling you more about themselves than the painting. This new track I’m on certainly holds to that belief and expands horizons and parameters into joy, newfound energy and excitement.”

— Cathy Moser

Rocky Hawkins Taking on the shelled breath of those who may have ventured off trail, the whispered stories never told, grasping the leftover shadows of dusty horizons, the blood, bone and flesh of distant moments gently balanced on the tip of his brush, Rocky Hawkins amplifies the spaces between truth and revelation.

Stepping into a Hawkins painting is like wandering inside a dream; there is a sense of otherness, and yet there is a blanket of belonging and belief, seduction and surrender. He is telling us the stories without the moral, describing scenes without destination, and most of all he is introducing characters that linger on after the book is closed.

“My relationship with shapes and colors is a combination of everything I’ve been through in my 59 years,” he says, walking up a trail from his home to his studio. “I’m carving out memories and thoughts and I’m taking risks all the time.”

Hawkins’ studio, atop a hill overlooking the vast unending Montana landscape, is part alchemy and part inspiration.

The studio is set up with an alcove dedicated to Hawkins’ smaller oil paintings, a larger custom space for his bigger pieces and standing between the two stations is a large pad on an easel, where he unlocks his ideas — a kind of pre-painting, somewhere between sketching and applying paint, a limbering up area.

He takes some black tempera and squirts it in a plastic container.

“I’m trying to get a glimpse, a feel for the paint,” he says, bringing the brush to the paper. “I’m looking for something that I can bring to the painting I’m working on.”

His strokes are, at first, aggressive, slightly out of control. His voice drops to barely a whisper, as the work simmers underneath his tutelage.

“I’m connecting shapes,” he says, continuing to explore. “This could be a face.”

He shadows in two eyes. A nose. A slash for a mouth. His brush, scratching at the paper, darkens one side with a determined downward motion. He moves like a gathering of clouds. “If I had another color …” and he grabs a tube of white. The air is electric. The process, so personal and yet so accessible, seems like a current conjuring a heartbeat from the earth.

“I just allow myself to experience the intensity, to take the risk,” he says, using the white paint to erase parts of the painting. “It’s exciting. The act of creating this leads to the real painting.”

His voice quiets again, as he allows the piece to draw him into painting. It is as if he’s calling to the canvas, and it answers him. He’s not staying within the limits and sloshes the brush, heavy and wet with blackness, across the surface, dripping paint, a life force. Moving from the pad to the 40- by 40-inch canvas, set into his self-designed moveable easel, he’s ready to translate. Taking a knife he works quickly, racing his ideas from his mind to his brush, grabbing the white and carving it into the surface, finding his way as he goes. Soon a face appears, not quite the one on the pad but a man, perhaps a brother with the same countenance of determination.

“I am completely open to the moment,” he says, riding the wave of his process. “I go into each piece not knowing where it will end. It’s a journey into the unknown. And if I know my way, then it’s not worth doing. The minute I start thinking too much, it can go bad. The best actions are spontaneous, it’s like dancing within the painting, and I lose track of time.”

Hawkins has no desire to recreate Western history, but instead he filters the landscape, the history of the West and the people who crossed this way before, through his work.

“I need to express myself as an individual,” he says. “My paintings are more about feeling, not identifying a specific image.”

There is an unmistakable voice in every Hawkins painting. Recognizable at once, his emotional connection to each piece, each aspect, his relationship to the colors — always surprising and alive — his work contains a spark, sometimes an ember, sometimes a blaze, but nevertheless it emits a vitality that comes across without fail.

One of Hawkins’ motivations for moving away from the typical Western genre is his belief in the need for change, for looking at the world as it stands, not as it was. This is something he shares with friend and mentor, Oleg Stavrowsky.

“I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say we’ve both been to the dark side of the moon,” Hawkins says. Colleagues for more than 25 years, Stavrowsky’s paintings still inspire Hawkins. “They express explosive action with brush strokes that seem to dance a battle with color and edges, yet in the end there is always this mysterious rhythm that allures my senses. There is a haunting beautiful weirdness in his abstracts that always attracts my curiosity. His inventiveness, passion and energy continues to spark the power of his art in me.”

And Stavrowsky says that Hawkins is the only artist he knows in the Western genre who is trying to do what he does.

“We came together because of that,” Stravrowsky says. “We’re trying to combine Realism with Abstract, but we’re trying to combine it on an equal basis. We want to introduce stunning Abstract work into that, to stretch the parameters. It’s very exciting for both of us. We feel we’re pioneering something. As far as Rocky goes, his ability to come up with fresh composition is unparalleled. His work is stunning. You can’t not look at his paintings, they’re so powerful. He owes nothing to anyone, he does his own thing, regardless of who approves of it.”

It’s Hawkins’ rebellious nature that has always attracted Stavrowsky to Hawkins’ work.

“He tickles it and plays with ideas until it becomes a painting,” Stavrowsky says. “He disregards all rules and laws and it always comes out very well designed. He has courage. Nothing will stop him. He paints what he feels.”

Mark Tarrant, owner of Altamira Gallery, in Jackson, Wyoming, is holding a solo exhibition of Hawkins’ work this summer, with an opening reception on July 15th.

“Lost At Last is an important exhibition of new work from Rocky Hawkins,” Tarrant says. “His paintings are exactly the kind of contemporary, cutting edge art people expect to find in Jackson Hole. It is a must-see event.”

Back in the studio, Hawkins, caught in the rapture of the piece, listens intently to his inner process while electronic music mixed with jazz settles on the space like dust. The black slashes from the “sketch” translate into a cascade of hair.

“I’m taking elements of what looks good next to what,” he says, using a knife fat with blue, blazing it down one side. “What am I saying here? What is it about? I don’t know.”

And that is the secret. The telestic. It’s what pulls him to the studio day after day and what sends him back home fulfilled at night.

“Strange things can happen here,” Hawkins says, using a dry brush to soften an edge. “It’s a frontier.”

— Michele Corriel

Cathy Moser lives in central Montana’s Judith Mountains where she writes about Western art, history, lifestyles and the outdoors.

Michele Corriel is a freelance art writer who enjoys engaging her poetic style as a basis for conveying the essence of the creative process in the visual arts. Published regionally and nationally, Michele has received a number of awards for her non-fiction as well as her poetry. Her first book will be out this year.

- Oleg Stavrowsky, “Yard Boss” | Mixed Media on Canvas | 19 x 24 inches

- Rocky Hawkins, “Cloud Warrior Sun Shield” | Acrylic on Canvas | 30 x 48 inches

- Rocky Hawkins “Keeper of Souls” | Acrylic on Canvas | 48 x 60 inches

- From above left: Rocky Hawkins, Oleg Stavrowsky | Photo: Kat Hawkins

- Oleg Stavrowsky, “Vanishing Indian” | Mixed Media | 20 x 28 inches

- Oleg Stavrowsky, “Comanche Royalty” | Mixed Media on Canvas, 30 x 42 inches | “For Comanche Royalty I’ve implemented turbulent abstract brushwork, color and design to reflect the history, immovable will and the many personality facets of this great Comanche leader.”

- Rocky Hawkins, “Red Eye” | Acrylic on Canvas | 36 x 48 inches

- Rocky Hawkins, “Ride From Gray” | Oil on Panel | 8 x 9 inches

No Comments