08 Mar The Western Nocturne

What happens when the lights are turned off? “When you’re a little kid, that’s when the monsters come out,” says Western painter Grant Redden. When you’re older, a moonlit night can bring a sense of peaceful quiet and mystery. Both feelings, and many in between, are evoked in nocturnes, or paintings depicting nightfall and lit by the moon, stars, a campfire, or even lamplight through a cabin window, and Western artists have a rich and enduring tradition of portraying these nighttime scenes.

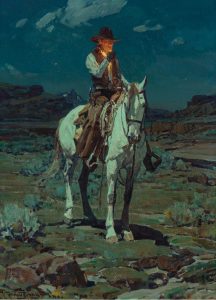

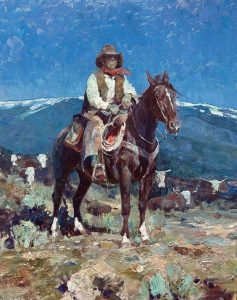

Frank Tenney Johnson, A Light in the Night | Oil on Masonite | 20 x 16 inches | 1936 | Private Collection | Courtesy of Heritage Auctions, HA.com

For many, the Western nocturne is epitomized by Frank Tenney Johnson’s A Light in the Night (1936.) The iconic oil painting depicts a lone cowboy sitting quietly on a horse, the starlit scene punctuated by the orange glow of his cigarette. After being immediately drawn to that point of light, the viewer’s eye wanders around the rest of the scene, gradually discovering more detail, as eyes do after adjusting to the dark.

Johnson and Frederic Remington set the standard for the Western nocturne in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with James Abbott McNeill Whistler as an earlier East Coast inspiration. Whistler’s moody, impressionistic nighttime scenes often featured water.

Among other historic Western artists who explored nighttime’s depths was illustrator and painter William Robinson Leigh. His 1915 Keams Canyon, Arizona, for example, depicts a Hopi adobe home with a few bright stars piercing the darkness above and a striking lone glowing window.

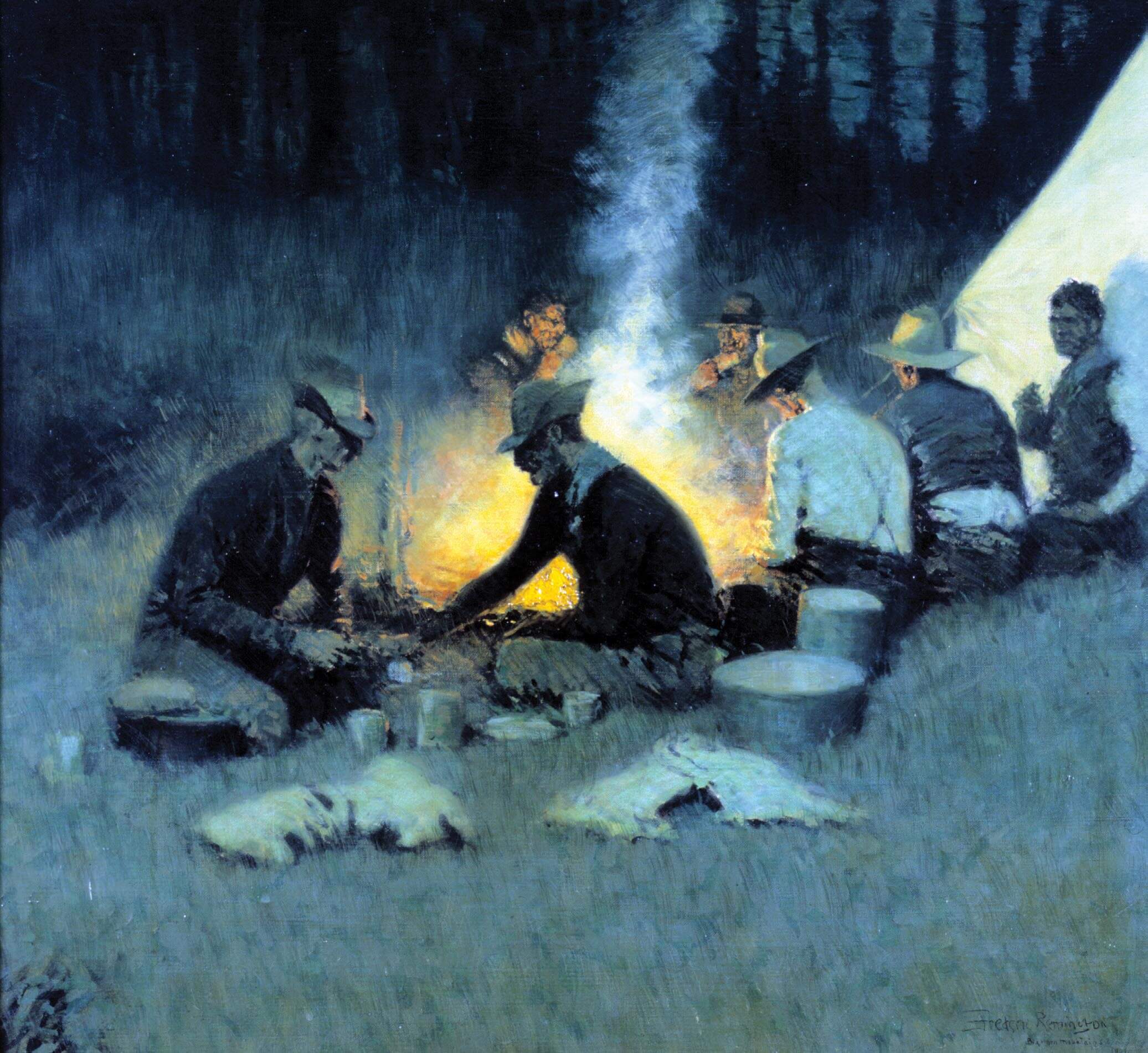

Frederic Remington, The Mess Tent at Night | Ink Wash on Paper | 1890 – 1891 | Courtesy of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming; Whitney Western Art Museum; 11.72

Printmaker Alice Geneva “Gene” Kloss, who arrived in Taos in 1925, also explored images at night. Her scenes of Taos Pueblo are alive with shadowy figures lit by unseen fires. While nocturnes in black and white are rare, Kloss was an expert in her medium, says Susan F. Barnett, the Margaret and Dick Scarlett Curator of Western American Art at the Whitney Western Art Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center in Cody, Wyoming. “She creates a beautiful sense of chiaroscuro, the light coming out of the dark.”

Without bright light, nocturnes must contain softer edges, fewer details, and a more abstract quality. For Remington, Johnson, and other Western artists who previously worked as illustrators, the nocturne helped move them into fine art by freeing them from a sharp-edged, highly narrative style. “It was the opportunity to be less anecdotal, to create drama without necessarily having actors on the stage, or at least to diminish the role of human actors. The nocturne plays up the power of nature,” Barnett says.

William Robinson Leigh, Keams Canyon, Arizona | Oil on Canvas Board | 12.125 x 16.125 inches | 1915 | Courtesy of the Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, OK; 01.133

The power of nature at night includes the unknown, the mysterious, and an element of hidden danger. Sight is diminished, and other senses become more acute. Because representational Western art invites viewers to imagine themselves within a scene, a skillfully rendered nocturne encourages us to become quiet and pay closer attention to the less obvious aspects of a painting, notes Seth Hopkins, executive director of the Booth Western Art Museum in Cartersville, Georgia.

Yet action and human drama can still be part of a nocturne, as Remington demonstrated in paintings of riders being fired on at nightfall or cowboys running with a herd during a stormy evening. Even by lamplight, the artist invoked a sense of subtle intrigue, as in The Mess Tent at Night, an ink wash on paper in which hungry cowhands, some with their backs to the viewer, are lit by an unseen lantern on the table. The work’s immediate, lively style leads Barrett to believe Remington likely produced it on location.

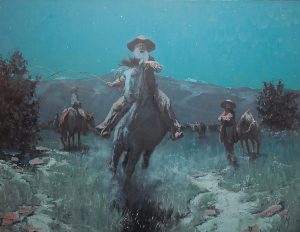

Michael Ome Untiedt, The Irrepressible Vigor of the Cowhand from La Mancha | Oil on Linen | 20 x 24 inches | Private Collection

Today, Western artists carry on the evolving nocturne tradition, many of them inspired by the genre’s early greats. Michael Ome Untiedt remembers being spellbound by the 2003 exhibition Frederic Remington: The Color of Night at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. A few years earlier, Untiedt had painted his first night scene. Since then, the Colorado-based artist has become known for his nocturnes, which constitute a large portion of his work. Most are painted from imagination, with reference photographs for details including anatomy.

Among these is The Irrepressible Vigor of the Cowhand from La Mancha. Taking its inspiration from Miguel de Cervantes’ 17th-century novel Don Quixote, Untiedt’s painting depicts a white-haired cowboy readying his lasso as he rides full-steam toward the viewer. In the moonlit background, his fellow cowhands and the cattle stand looking at him, clearly wondering what this impassioned but misguided fellow is doing. For the artist, the painting suggests that just as Quixote attempted to live the myth of the chivalrous knight, our ideas of the Old West cowboy life are largely romanticized myths.

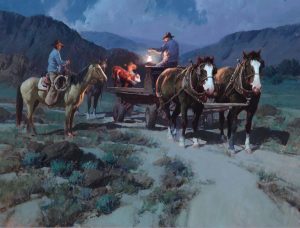

Bill Anton, Deep in the Wind Rivers | Oil on Linen | 36 x 42 inches

While nocturnes allow artists to be more creative and inventive, one element must be in place: colors that make us believe it is night. “The control of color is paramount. You must invent the color, but you have to be extremely judicious,” says Arizona-based painter Bill Anton, who has earned numerous awards for his night scenes, including the Frederic Remington Painting Award at the Prix de West at Oklahoma City’s National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum for Makeshift Ambulance. “As actual moonlight is very, very gray, you must interpret and inject some color which isn’t really there, but in so doing, you can’t cross the line into phony chroma and paint a blue-green day scene,” Anton says.

Bill Anton, Makeshift Ambulance | Oil on Linen | 34 x 46 inches

This is a challenging task that both historical and contemporary artists have worked to overcome. Remington often spoke of using his Kodak camera, and some art historians theorize that he may have experimented with the use of flash photography to capture outdoor scenes at night, says Michael Grauer, McCasland Chair of Cowboy Culture and Curator of Cowboy Collections and Western Art at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. While a flash distorts the night’s true colors, Remington was skilled enough that if he did refer to such a photograph, he would have known how to adjust the colors, Grauer says.

Anton believes Remington would only have used flash for simulating firelight rather than moonlight. “A flash would have shown him how light coming from the ground uniquely illumines a dark figure far differently than moonlight coming from above,” he says.

Grant Redden, Nocturne | Oil on Panel | 20 x 16 inches

Understanding how to adjust a painting’s color scheme for a nocturne involves spending significant time outdoors at night, observing and taking note. When painter Grant Redden’s children were young, he would dress them in a different solid color and take them on walks in bright moonlight, noticing and remembering how each hue appeared. He uses this store of knowledge to successfully transform daylit scenes into nocturnes through color, value, shadows, and the softening of edges and elimination of detail.

Redden’s painting Nocturne was a compelling challenge, he says, because it features a black horse at night. Yet even without dark on dark, nocturnes inherently contain much closer color values than bright scenes. Redden considers them a form of tonalism, an approach that uses a limited color palette and emphasizes mood and atmosphere, often with a hushed or melancholic feel.

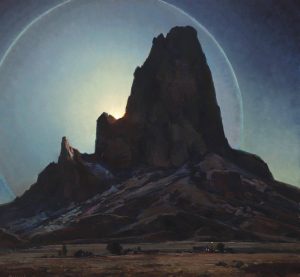

Josh Elliott, Otherworld | Oil | 28 x 30 inches

The ability to conjure this dreamlike timbre and sometimes ethereal realm is reflected in landscape painter Josh Elliott’s Otherworld. The image began with a small nighttime plein air study of Agathla Peak, south of Monument Valley in Arizona. The striking landform in the moonlight was interesting, but it lacked something, Elliott says. A few months later, near his home in Helena, Montana, he witnessed an enormous lunar halo. He added a moon halo to the study and liked it so much that he recreated it as a larger painting. The title refers to the moon as separate from our planet, he says. But it also speaks of the artist’s feeling as a visitor to a sovereign nation when spending time on the Navajo Reservation or other tribal lands.

Working on location, Elliott mixes colors by headlamp. He remembers where each sits on his palette and then turns off the light and allows his eyes to adjust to the night before he paints. Many artists avoid using any artificial light, and Anton is among them. Instead, he drew on decades of experience to create Deep in the Wind Rivers, an especially challenging painting because it contains two light sources, a campfire and the moon. With a couple of men close to the fire and others farther away, the artist had to render each one as lit by both sources but in proportion to their distance from the fire. “So, it was all interpretive and quite a balancing act,” he says. “As soon as I got into the painting, I knew I was over my head. I called on some divine assistance on that one.”

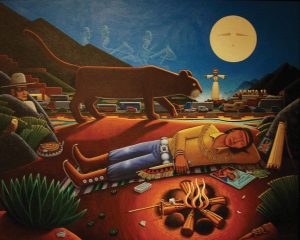

David Bradley, Tonto’s Dream | Acrylic on Canvas | 48 x 60 inches | Courtesy of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming; Whitney Western Art Museum; 8.13

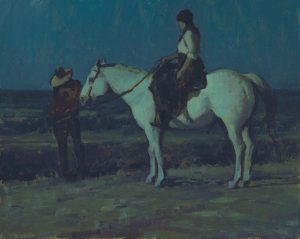

California-based painter Glenn Dean’s nocturnes are produced through careful observation, color notes, written notes, photo reference, and memory, such as with The Messenger depicting a woman sitting quietly on a white horse facing a man who stands with his head down, as if wiping a tear from his face. “It’s a unique world at night, so I’m likely to use all means necessary to make a convincing picture,” he says. “There’s a dreamlike spell that the moonlight casts on everything. This light has an emotional, poetic quality that is quite subtle and can make it difficult to distinguish one shape from another, one object from another, creating a beautifully abstracted, obscure world.”

Although the term nocturne may call to mind traditional Western scenes, contemporary painters have stretched the genre in new directions. Barrett notes that the reclining figure in Tonto’s Dream by Chippewa artist David Bradley, for example, suggests inspiration from late 19th-century French painter Henri Rousseau’s painting The Dream. Bradley’s moonlit scene, filled with symbolism, also features the Lone Ranger, a casino, traffic in the distance, and ghost riders in the sky.

Glenn Dean, The Messenger | Oil | 12 x 15 inches

Kim Wiggins produces nocturnes in his signature, almost Van Gogh-like expressionistic style, while Mark Maggiori pushes the intensity of color and contrast even in night scenes. Tom Gilleon bridges the contemporary and traditional with paintings of tipis glowing from within against the night sky. Referring to these more contemporary nocturnes, Hopkins says, “The Western art tent is bigger than many think, and it can still be bigger.”

No Comments